Engines need to breathe the same way that humans do. To make this possible, engines rely on a couple of systems to ensure that enough air is entering the system while harmful vapors are expelled or redirected. This includes the positive crankcase ventilation (PCV) system.

A Quick Background on the PCV Valve

Before mass airflow (MAF), even on fuel-injected systems, the PCV valve applies a controlled manifold vacuum to the crankcase, which lowers the pressure so that outside air can enter the crankcase through its closure hose through a small air filter element in the air cleaner or even built into the oil filler cap.

On MAF systems, the PCV flow needs to be measured as part of total airflow, so the PCV closure hose is connected to the air inlet tube between the MAF sensor and the throttle body.

Note: If you have a MAF system, you don’t have a crankcase breather.

The Basics of Crankcase Ventilation: What Is a PCV (Crankcase) Breather?

Blowby is a common problem found in many (if not all) vehicles. This occurs when gases and unburned fuel leak past the piston rings and into the crankcase.

When the engine is running, combustion pressure forces the piston downward, causing combustion by-products like hydrocarbons and water vapor created during combustion to leak by the piston rings. A sealed crankcase will build pressure and blow seals.

Pre-1960s engines had a draft tube to release the blowby pressure, but in 1962, Chevy put a PCV valve with a closure hose and a crankcase breather on the Corvair.

Today, every vehicle has some type of PCV system. The unburned hydrocarbons inside the crankcase can’t be vented into the atmosphere due to pollution concerns, posing a problem that manufacturers have tried to solve.

Some systems use an oil/vapor or oil/water separator instead of a valve or orifice. These are usually the PCV systems found in turbocharged and fuel-injected engines.

PCV Valve-Controlled Systems

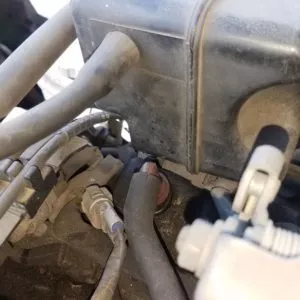

Most PCV valves are one-way valves with a spring-operated plunger, which controls the valve flow rate. The PCV valve is often found in the valve cover or intake manifold.

The PCV valve regulates airflow through the crankcase. Under high speeds and heavy loads, the PCV valve opens, allowing maximum airflow to enter the engine. The PCV valve also prevents the high intake manifold vacuum from drawing oil from the crankcase and letting it flow into the intake manifold.

If the engine backfires, the valve will close to prevent a crankcase explosion.

Orifice-Type PCV Systems

Some PCV systems use a calibrated orifice instead of a valve, which can be integrated into the valve cover or in-line (like the Corvair PCV valve) in a hose that connects the valve cover, air cleaner, and intake manifold.

Orifice flow control systems do not rely on the remaining fresh air inside the crankcase. Instead, the crankcase vapors are drawn into the intake manifold in amounts that correspond to manifold pressure and orifice size.

Separator Systems

Some turbocharged and fuel-injected engines use an oil/vapor or oil/water separator and a calibrated orifice instead of a PCV valve. These engines rely on the air intake throttle body for crankcase ventilation vacuum.

Symptoms of a Bad PCV System

If you’ve driven a vehicle with a carburetor and a round breather, you might have noticed that there is a hose from one valve cover or the oil filler cap connected to a small filter inside the breather housing.

That’s the crankcase filter. If you see engine oil in that filter or in the air cleaner, that means the PCV system isn’t flowing as it should and the crankcase blowby is making its way to and through the filter into the air cleaner.

When you disconnect the closure hose for the PCV system with the engine idling, you shouldn’t see steam and vapor there. You should feel a slight vacuum at that hose. You can check that with your finger or a piece of paper.

If you see steamy vapor at the closure hose with the engine idling or no slight vacuum, check the vacuum supply to the orifice or PCV, and check to see if the orifice or PCV valve are clogged.

Remember: engines take air and vapor into account when calculating air-fuel mixture. The PCV breather is responsible for ensuring that intake air flows freely in the engine, so, again, a problem with the PCV system will ultimately result in drivability problems, such as:

- Rough or unstable idle (not usually)

- Excessive oil consumption (if the PCV valve is stuck wide open or the orifice is too big)

- Oil in the air filter housing

- Oil leaks due to excessive crankcase pressure

PCV-Related Diagnostic Trouble Codes (DTCs)

Aside from drivability issues, the powertrain control module (PCM) will also store diagnostic trouble codes that will alert you via an illuminated check engine light when something is wrong with the PCV system.

Diagnostic Trouble Code P0101

If DTC P0101 pops up on the OBD-II scanner, it usually means that there’s an airflow circuit range problem. In most cases, a defective PCV valve or an MAF circuit fault can trigger this code. Fuel trim codes may also result depending on the type of PCV system concerned.

Diagnostic Trouble Code P0505

If DTC P0505 is presented in the OBD-II scanner, it means that there’s a problem with the idle control system. A defective PCV valve or problems with its hose or connections can trigger this code.

PCV System Diagnosis

If you suspect that faults in the PCV system are holding your vehicle back from performing its best, here are some tests that you can perform to confirm your diagnosis.

Rattle Test

Conducting a rattle test is one of the simplest diagnostic tests you can do to determine whether or not there’s a problem with the PCV system.

To do this, remove the PCV valve (if it has a plunger and a spring inside) and give it a shake. If no rattling noise can be heard, it means that the valve is defective (clogged or stuck) and should be replaced.

But if the PCV valve produces a rattling noise, that doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re in the clear.

The PCV valve springs might still be intact, but they can get brittle over time, so you should still consider replacing the valve, which is typically affordable, but make sure you get exactly the right one.

Warning: Two PCV valves that look the same may have different flow rates, which can cause fuel trim related trouble codes.

3X5 Card Test

To perform the 3X5 card test, hold a 3X5 card or any piece of paper of the same size and hold it over the end of the crankcase closure hose.

Snap-Back Test

The snap-back test involves placing one finger over the inlet hole in the valve and removing it rapidly while the engine is running.

The valve should snap back after doing this motion a couple of times. If it doesn’t you need to replace it with a new one.

Crankcase Vacuum Test

To perform a crankcase vacuum test, first disconnect the closure hose from the crankcase filter or air inlet tube and cap it.

The next step is to remove the oil dipstick and connect a water manometer or gauge to the dipstick tube.

Then, start the engine and observe the gauge at idle and at 2,500 rpm. The gauge should show that a vacuum is present at 2,500 rpm.

Any information provided on this Website is for informational purposes only and is not intended to replace consultation with a professional mechanic. The accuracy and timeliness of the information may change from the time of publication.